Published on June 12, 2024

A prom queen drenched in pig’s blood. A crazed husband smashing through a bathroom door. A demonic clown lurking in a sewer.

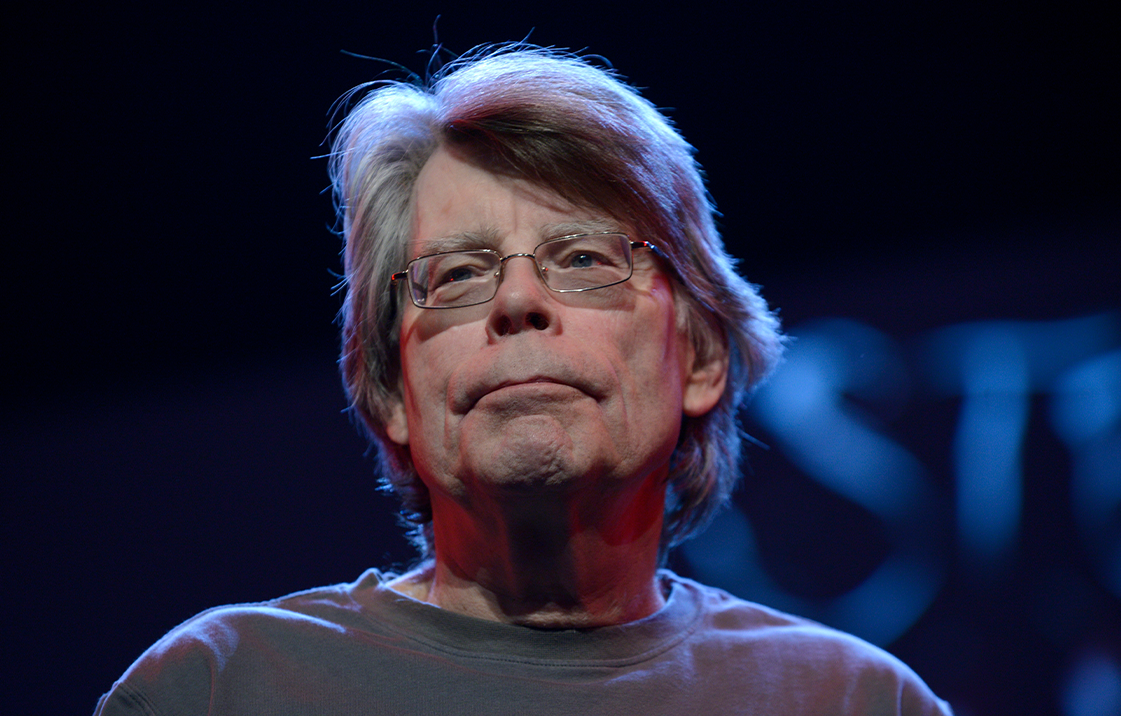

Whether encountered on page or screen, Stephen King has created some of the most enduring horror images of the twentieth century. Since the publication of Carrie in 1974, the bestselling author has terrified readers and viewers for fifty years.

In his non-fiction work Danse Macabre (1981), King writes that good horror “functions on a symbolic level, using fictional (and sometimes supernatural) events to help us understand our own deepest fears”.

King remains as relevant today as he was in the 1970s because his fictional worlds disrupt, disorient and even terrorise our understanding of ordered, benign and safe societies.

Across his horror work, King focuses on the effect that evil or the supernatural can have on the home and the hometown. Adhering to classic Gothic and horror tropes, the home and hometown are not safe places in King’s works because they are repeatedly under threat from external forces.

Arts & Culture

Provocative women in cinema

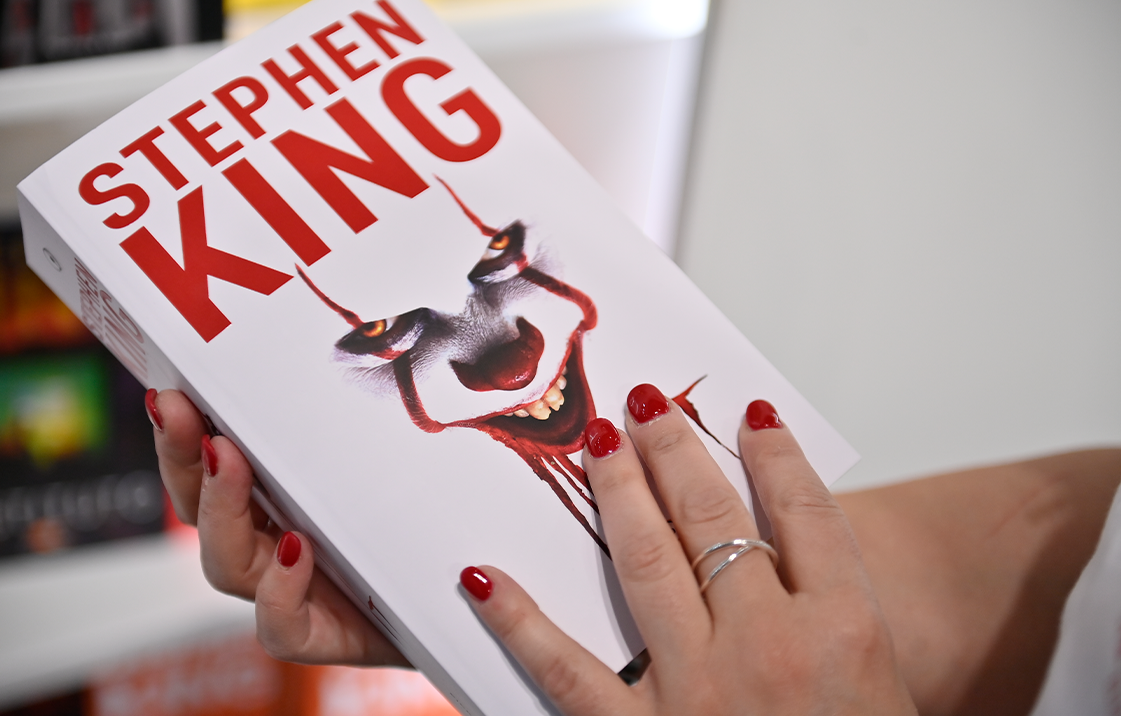

For example, in Salem’s Lot (1975), a modern Dracula transforms the population of Jerusalem’s Lot into vampires, and in It (1986), a shapeshifting monster from an alternate universe attacks the town of Derry every 27 years.

These and many other King stories are set in fictional towns in the US state of Maine, influenced by his own upbringing there. These towns may not be real, but King’s authentic depiction of suburbia reminds readers that these horrors could puncture the safety of their hometowns too.

Not all threats are external – the small town and the domestic can also be a source of evil in King’s works.

His novels and short stories are full of seemingly benign figures who become monstrous: the teenage girl turned telekinetic murderer (Carrie); the father driven mad with cabin fever and ghostly possession (The Shining, 1977); young children sacrificing adults as part of a demonic cult (Children of the Corn, 1977).

His horror demolishes our assumptions that the father is a protector, and that the child is an innocent.

While supernatural, these domestic and familial monsters horrifically express real-world societal problems, including alcoholism, domestic violence, bullying and religious extremism. Even an outside evil like Pennywise the clown (It) functions on a symbolic level to represent the racism, child abuse and homophobia within the small town itself.

King doesn’t hold a looking glass to society but a funhouse mirror, twisting societal fears until they take on non-human shapes.

King’s first novel Carrie is a prime example of his small-town monsters being both a product of and threat to the home. Bullied by her classmates and abused by her Christian fundamentalist mother, 16-year-old Carrie White catastrophically unleashes her telekinetic powers on the town of Chamberlain, killing 440 people after she is subjected to the infamous pig’s blood prank at prom.

Speaking to the New York Times in 2016, King said “people saw Carrie as an extreme case of what they went through in high school”. She is both the underdog, taking out revenge on her high school bullies and repressive mother, and the villain, grinning “like a death’s head” as she makes the whole town pay for her mistreatment.

Crucially, King writes this monster with empathy, showing how the bullying and abuse has led to Carrie’s physical manifestation of rage. As a postmodern work, Carrie moves between third person narrative, internal monologue, survivor testimony and autobiography, academic publications and news reports. King, the townspeople and the reader all attempt to piece together these fragments into a coherent whole that explains Carrie’s paranormal abilities and the cause of her violence.

In response to the misogynist bullying and abuse that ridicules her weight and punishes her for starting her period, film scholar Vivian Sobchack is right to read Carrie’s vengeance as “an apocalyptic feminine explosion of the frustrated desire to speak” against a patriarchal American society.

The abuse Carrie faces in the 1970s still resonates today in a world that shames young women for their bodies and desires and restricts their reproductive rights.

Despite the townspeople’s attempts to understand Carrie, King does not provide a meaningful answer or resolution. Often in the horror genre the plot is resolved and normative values are restored: the monster is vanquished; there are survivors after the serial killer attacks.

However, King’s work is what horror scholar Linda J. Holland-Toll calls ‘disaffirmative’ because there is often no redemption or return to normal. At the end of Carrie, all that is left is destruction, “a blackened and shattered hub” of a town “suffering from terminal cancer of the spirit” after so much violence from and towards their own children.

Introducing his collection Just after Sunset (2008), King states, “I didn’t want to write about answers, I wanted to write about questions”.

At the end of King’s stories, we are left with more questions about how such evil could be prevented, our complicity in it and how a community can possibly heal. King’s work may be fantastical entertainment but alongside the scares is a real existential and social terror that makes his work endure today.

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.