Published on May 28, 2024

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of people who have died. It also includes distressing descriptions and derogatory terms for Indigenous people used in their historical context.

In 1943, at the height of World War II, Wilfred Agar, professor of zoology, geneticist, and dean of the Faculty of Science at the University of Melbourne, released a blueprint for a healthy, prosperous and happy future for Australia.

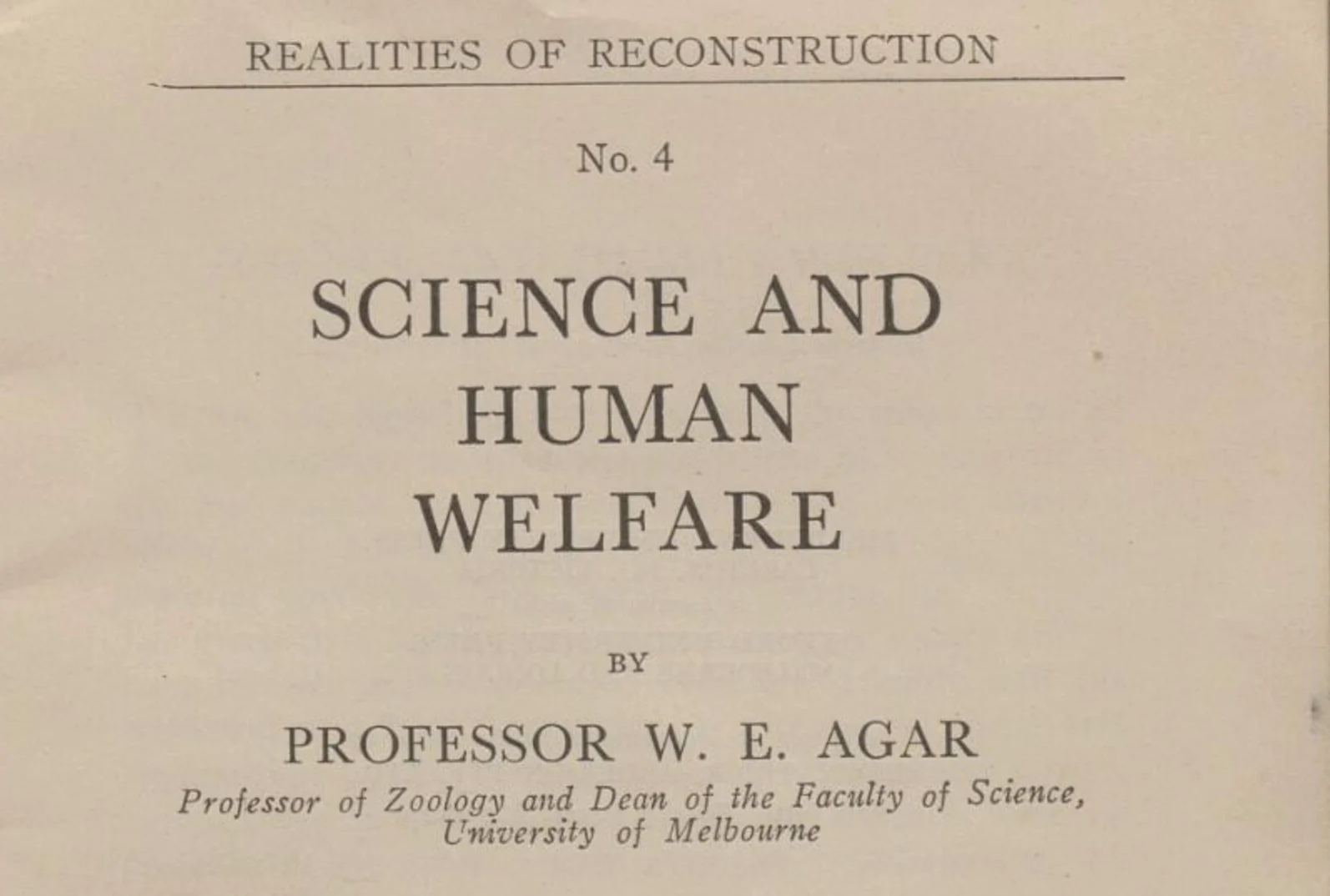

The booklet, Science and Human Welfare, was part of a series called Realities of Reconstruction, published jointly by Melbourne University Press and Oxford University Press. It argued for measures to restrict the breeding of less able (“mentally deficient”) Australians.

He cited sterilisation programs in numerous countries and remarkably singled out the German program for special favour.

A key, largely unspoken element in Agar’s contention concerned race. In the final footnote of his booklet, Agar explained that his calculus relied on immigration restriction to “only white peoples”.

Agar’s championing of ‘whiteness’ represented a considerable body of contemporary opinion. The “eugenic imagination” in the first half of twentieth-century Melbourne had no place for the ‘black’ Indigenous population in the ‘white Australian race’.

Sciences & Technology

The Boorong pride themselves upon knowing more of astronomy than any other

When eugenics was mainstream, the University made it so

Agar was president of the Eugenics Society of Victoria from its foundation in 1936 until the end of World War II in 1945. His predecessor as putative leader of the eugenic movement in Melbourne was another University of Melbourne professor, Richard Berry, who was professor of anatomy in the Medical School from 1906 to 1929 (and dean from 1925 to 1929).

Berry claimed that most criminals, slum dwellers, “full-blood” Aboriginal people and “coloured races” were mentally and racially deficient.

These views received almost total consensus in all the newspapers of the day.

The membership of the Eugenics Society of Victoria reads like a who’s who of the academic, judicial, scientific and educational elite of Melbourne society, the majority of whom had close ties with the University, and which included the vice-chancellor, Sir John Medley.

In fact, the Society was effectively an offspring of the University of Melbourne, and clearly Medley provided a sympathetic environment for it.

However, right up until the last decade or so of the twentieth century, material relating to the involvement of such public supporters of the eugenic movement was forgotten or ignored in biographical publications or entries.

The work of the Melbourne eugenicists produced specious justifications for racial science, drawing on a climate of racism that long predated it.

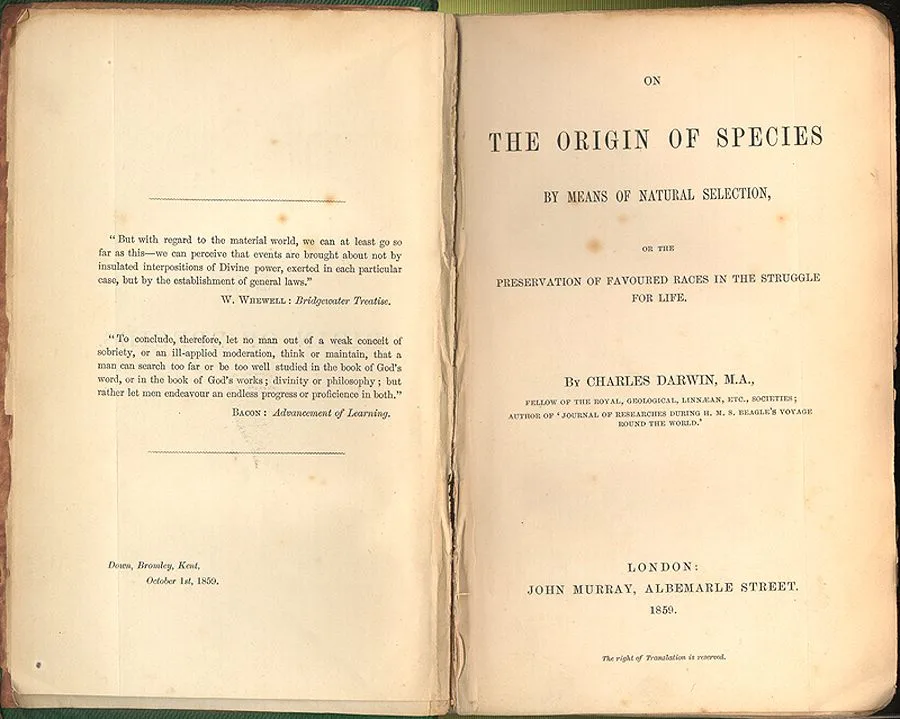

What is now called scientific racism appeared in the late eighteenth century and gained considerable intellectual ammunition after the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859, along with The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex in 1871.

Evolution came to be seen as one of the most important influences on biological, and therefore, human, history and development.

It became almost universally accepted that different races had different evolutionary pathways, and that the ‘black’ races were at an earlier stage of development than the ‘white’ races, with the ‘yellow’ in-between.

Health & Medicine

This has so rarely occurred in the University’s history

After some initial opposition at the University, ‘social Darwinian’ ideas, especially those relating to eugenics (the science of improving a race by selective breeding), quickly spread, especially after the arrival of Walter Baldwin Spencer as the first chair of biology in 1887 and then Richard Berry in 1906.

The University was to be central in this intellectual justification of the racial superiority of the white races, and in the program that effectively removed from the Indigenous population any consideration of fair or reasonable treatment or acceptance.

Post WWII, the world moves on but eugenics lives on

In Australia, eugenics virtually disappeared as a topic from newspapers.

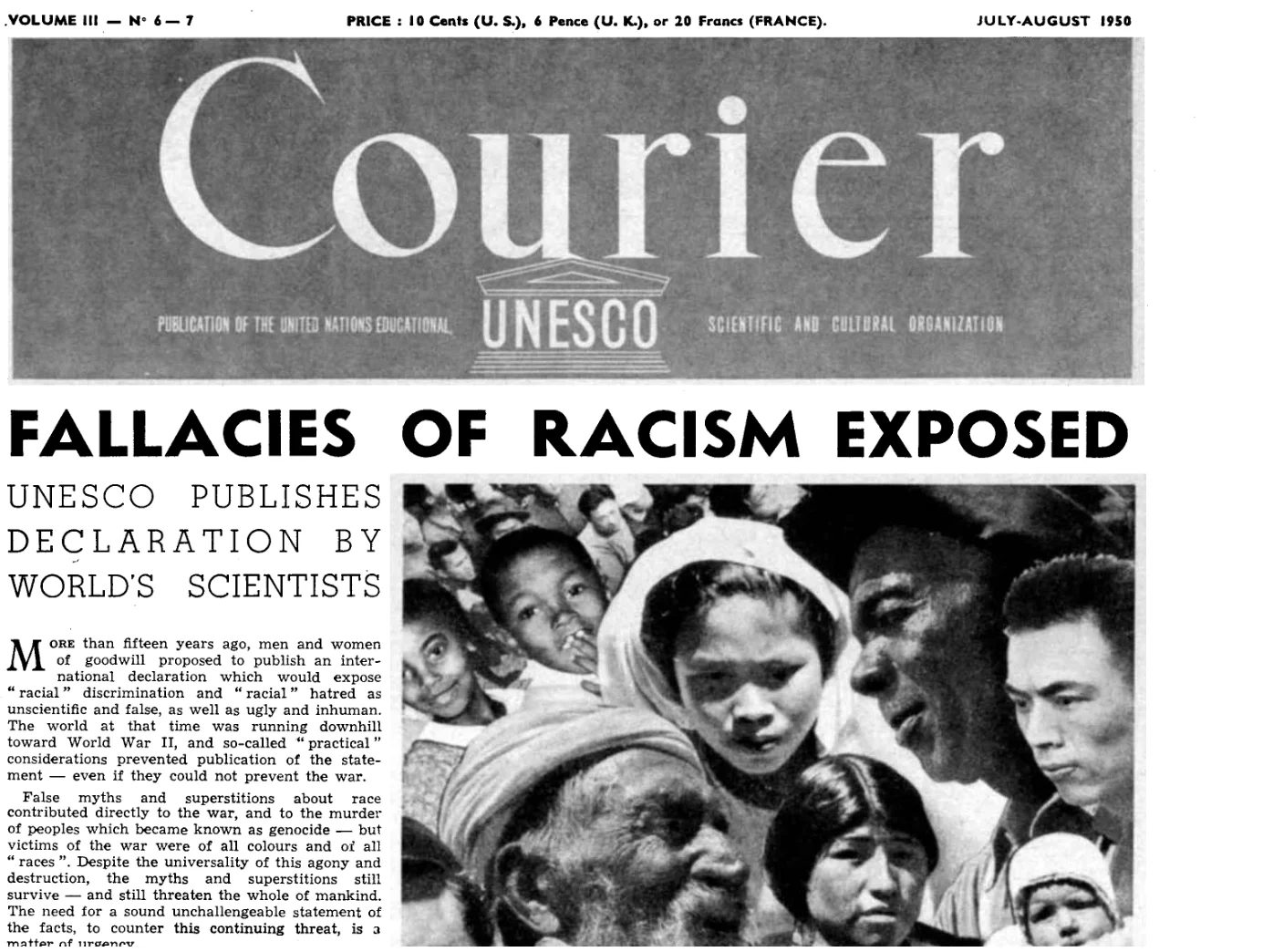

The popular rejection of the extreme form of eugenics was endorsed in the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) 1950 Statement on race.

Yet, on the evenings of 14 and 15 September 1977, at the invitation of an organising committee of the Faculty of Education, professors of psychology Hans Eysenck and Arthur Jensen delivered the Fink memorial lectures in Wilson Hall in the University of Melbourne.

In 1969, Jensen had published an article in the Harvard Educational Review that claimed intelligence was essentially heritable, accounting for 80 per cent of the effect. He also claimed that black Americans scored, on average, about 15 points (one standard deviation) lower than white Americans.

Eysenck had been Jensen’s mentor and teacher, and soon after he published a book backing Jensen’s argument.

In his lecture, Jensen made it clear that eugenics remained a subject of research at the University of Melbourne, arguing that a biological view of intelligence had made a triumphant comeback after the decades of disgrace after 1945.

After World War II, a group of eugenicists across Europe and the United States had attempted to distance themselves from the Nazi atrocities and distinguish between ‘good’ eugenics and ‘bad’ eugenics.

This has been the catchcry of many up until the present day.

In this history of the University of Melbourne, we can see that it is not always easy to distinguish between much of what was preached by the Eugenics Society of Victoria before the war and the views of its supporters after the war.

Postscript

The first Indigenous graduate at the University of Melbourne (and in Australia) was Margaret Williams Weir, who completed her Diploma of Physical Education in 1959, more than half a century after the first Māori graduate in New Zealand, Sir Apirana Ngāta, who was born in 1874 and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science in 1893 from Canterbury University College.

Before the 1950s, there was no prospect of Indigenous Australians enrolling at a university.

This is an edited extract from Dhoombak Goobgoowana – A history of Indigenous Australia and the University of Melbourne – Volume 1: Truth, published by Melbourne University Publishing and edited by Dr Ross Jones, Dr James Waghorne and Professor Marcia Langton. Hard copies are available to purchase, and a free digital copy is available through an open-access portal.

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.