Published on May 21, 2024

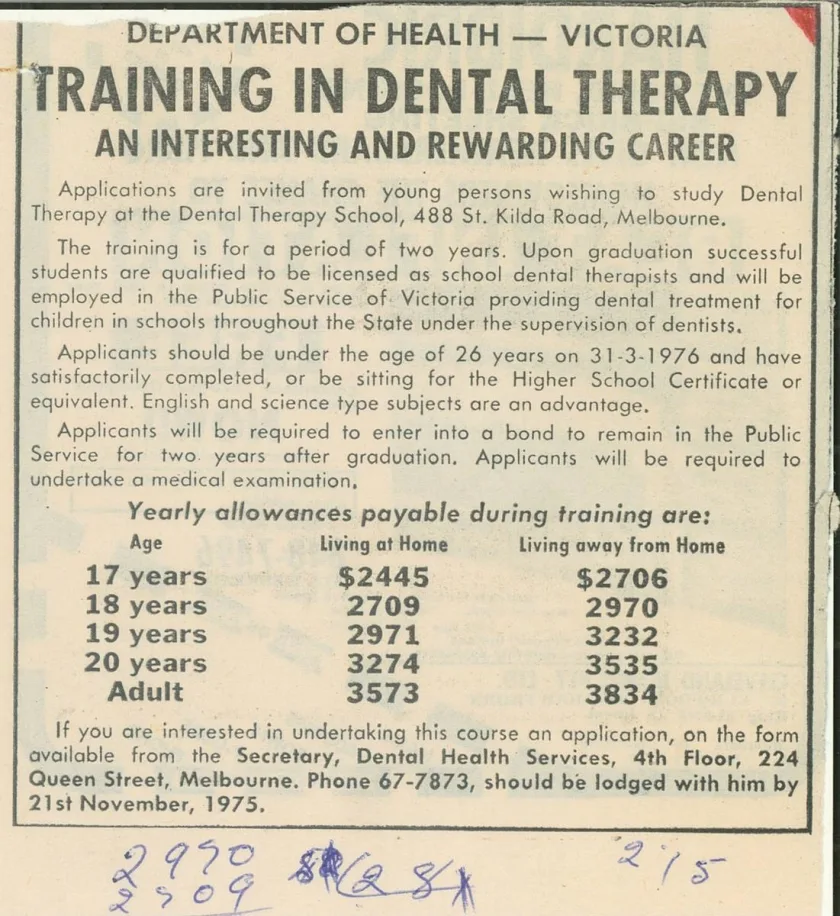

When I finished Year 12, nobody in my family had ever been to university. The options I could see in front of me were teaching and nursing – but I always wanted to do something a bit different in health. Then my mum spotted an ad in the paper, advertising training places for dental therapists.

I was a terrified dental patient myself as a young child, so I wanted to do a better job and look after children in a different way.

At the time, the Whitlam Labor government gave conditional grants to the states to set up universal school dental services, built on a New Zealand model, to be staffed by a new profession – dental therapists – to address the growing oral healthcare needs in the community.

Victoria was the last state to pick it up – the resistance here from dentists was considerable and very powerful.

I was 17, straight out of high school among the first group to be trained in Victoria.

It was a two-year course to be a dental therapist and it was set in a brand-new dental therapy school which went on to train over 500 dental therapists. It was a full-on course and you had to pass every subject or get tapped on the shoulder and asked to leave.

There was no opportunity for repeating!

You had to be right-handed, female, under 25 and unmarried to train as a dental therapist, and prepared to work anywhere in Victoria. We were ‘bonded’ to work for the School Dental Service for two years after our training.

We could do check-ups, x-rays, fillings, and extractions which was often a dentist’s bread and butter –it’s no wonder they saw us as a threat at the time.

Health & Medicine

Dental care and healthcare are the same thing

Every dental therapist I know takes great pride in the fact that we can provide really caring treatment of children. There were many children with high needs who came to us after they had been to several different dentists and were so scared that no one could treat them.

We treated many children who may never have received treatment otherwise and turned them into people who could have regular dental check-ups.

We had a very prevention-oriented approach and provided oral health education in the schools and communities we worked in.

Our patient’s parents would ask us to treat them too, but the regulations back then said we couldn’t treat adults. We were only allowed to provide treatment for primary and high school-aged children then.

The reality was, that dentists had a monopoly over the market at the time. This only started to change when the Federal Government introduced reviews of the legislation for anti-competitive behaviour.

The old legislative model was constructed to maintain occupational dominance by dentists. They wrote the rules, they sat on the boards, they had the ear of the government at the time, and they controlled the environment in which we practised.

Because of the cost of dental services and some of these restrictive market rules, there was a swathe of people missing out on dental care.

We saw a need to change the legislation to remove the age, supervision and employment limits and allow dental therapists and hygienists to work anywhere there was a need for their skills.

Health & Medicine

Healthcare has a waste problem, but we can achieve net zero

I had come straight out of high school into this profession and we didn’t know anything about public policy – but we learned. There were many barriers but also some tenacious dental therapists and public dental sector advocates who supported us.

Academia opened my eyes in new ways.

Getting the discipline education into the university sector meant dental therapists got an appropriately recognised qualification. We combined dental therapy and dental hygiene into a new profession – oral health therapy.

The other emancipatory pillars that propelled us forward were changing the regulations to open up the profession’s opportunities, usage and visibility, and seeing members of our profession start to do research in our discipline.

Importantly we also started to lead education and accreditation for our own profession.

One sliding doors moment for me was when a colleague saw an ad in the paper for the Victorian Women’s Trust, advertising grants to enable women to participate in public policy.

Neither of us had ever written a grant application before but we applied and were successful.

They gave us some funding that allowed us to employ an economist to do some modelling, demonstrating how we benefitted the community and a media advisor who helped us advocate for the changes.

That grant changed our ability to participate in policy making.

Today, you’ve got dental and oral health therapists working in oncology wards, in Aboriginal communities, in outreach programs, in public and private dental and specialist practices, in disability, aged care and special needs settings, academia and of course in community and school dental programs like Smile Squad.

Australia and New Zealand lead the world in oral health therapy education, discipline and practice.

I was the first female promoted to Professor in the Melbourne Dental School, but I’m more proud of the fact that I’m the first dental therapist to be made a Professor at the Melbourne Dental School.

I was also fortunate to be able to help establish this profession in the USA when I was invited to be on working groups to advise the US government on the development of dental therapy policy and curriculum.

Standing in front of Capitol Hill in Washington, working for the US Government was a “Woah!” moment. From a little ad in the paper to constantly having to explain what a dental therapist is, to advising US Congress on policy!

These days my work is more around improving oral health through community and Indigenous partnerships, and public and rural health which continues my interest in overcoming inequity – improving access to care for people who miss out.

Ours is a compelling story of occupational dominance, feminism and advocacy for improved equity in oral health, that has shaped a profession.

Decades later, we finally have a home for the story of dental therapy in Victoria with a new exhibition at the Medical History Museum to celebrate 50 years of dental therapists and their contribution to the community’s oral health.

This is thanks to Dr Jacky Healy, Director of Museums in the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, and Professors Mike Morgan and Alastair Sloan at the Melbourne Dental School.

The exhibition Shaping a profession: 50 years of dental therapists is at the Medical History Museum until Saturday 15 June 2024.

- As told to Danielle Galvin

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.