By Associate Professor John Fitzgerald

Published on July 3, 2024

Consider this conundrum.

It’s June 2024. An electronic dance music festival for 12,000 people, scheduled for later in the year at Melbourne's Flemington racecourse, has already sold out.

A conservative estimate is that around 30 per cent of the people attending the event will choose to take a pill or powder of unknown composition.

For context, that’s 3,000 young people putting an unknown drug into their bodies without knowing what's in it.

There is the capability and equipment to test some of these substances at this event and alert the crowd of young people as to what the substances contain.

So, you have a choice.

Do you:

(a) conduct the test before they use the substance or;

(b) conduct testing after they use the substance?

What would you choose to do? Which approach, pre- or post-consumption testing, is most likely to reduce harm?

This is the choice the Victorian State Government faced this year and I believe it’s one reason for the introduction of drug checking.

Faced with the liabilities of not saving a life when it could, any government (of any political persuasion) is obligated to introduce regulated drug checking.

The background to this ethical and empirical choice goes back to 2020.

Politics & Society

After the party

My colleagues Associate Professor James Ziogas, Professor Gavin Reid and I worked with a music event promoter on a proof-of-concept project funded by the University of Melbourne.

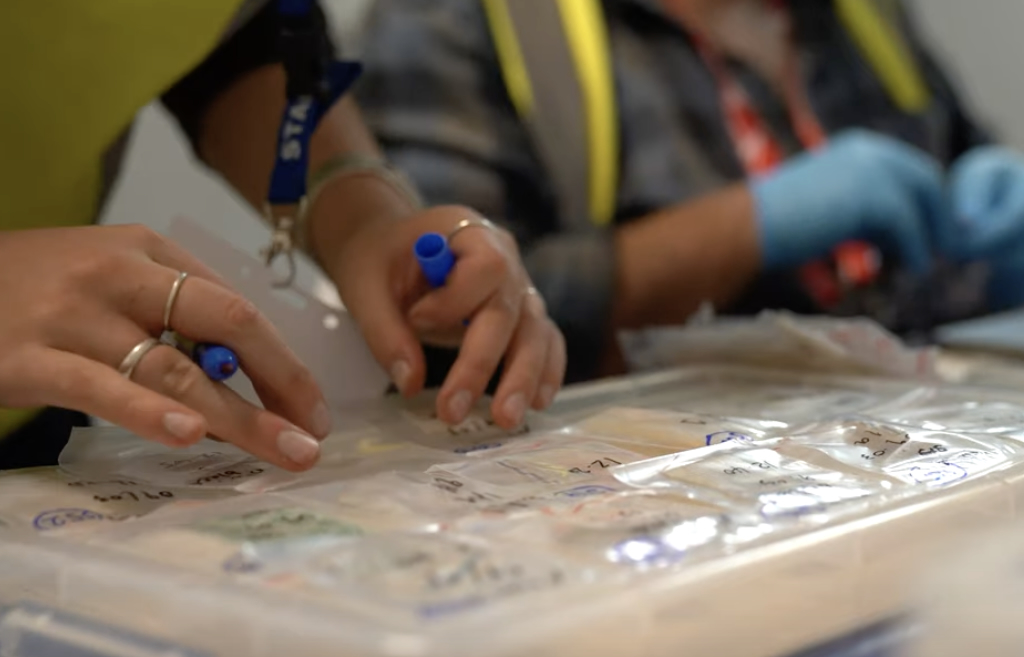

Our research demonstrated it was easy and feasible to collect several hundred small plastic bags used for drugs at a music festival and then test the drug residue.

We produced close-to-real-time drug monitoring and fed back those results to the first aid providers, event management and the government. We could also provide alerts about high-risk substances narrowcast back to festival attendees.

This is called post-consumption drug testing.

By 2023, government public health experts, the drug checking industry, key figures in the music festival industry and even the Victorian Coroner’s office knew about it.

But the young people at the event didn’t know much. All they knew is that occasionally they would get a warning on their social media about a dangerous substance at an event.

This is the consequence of post-consumption monitoring.

Those people choosing to take drugs at an event don’t get to make an informed choice.

If Government stayed with post-consumption testing, those 3,000 drug users at the festival at Flemington later this year would not get the choice to throw away a substance that is potentially deadly.

Politics & Society

A precarious high

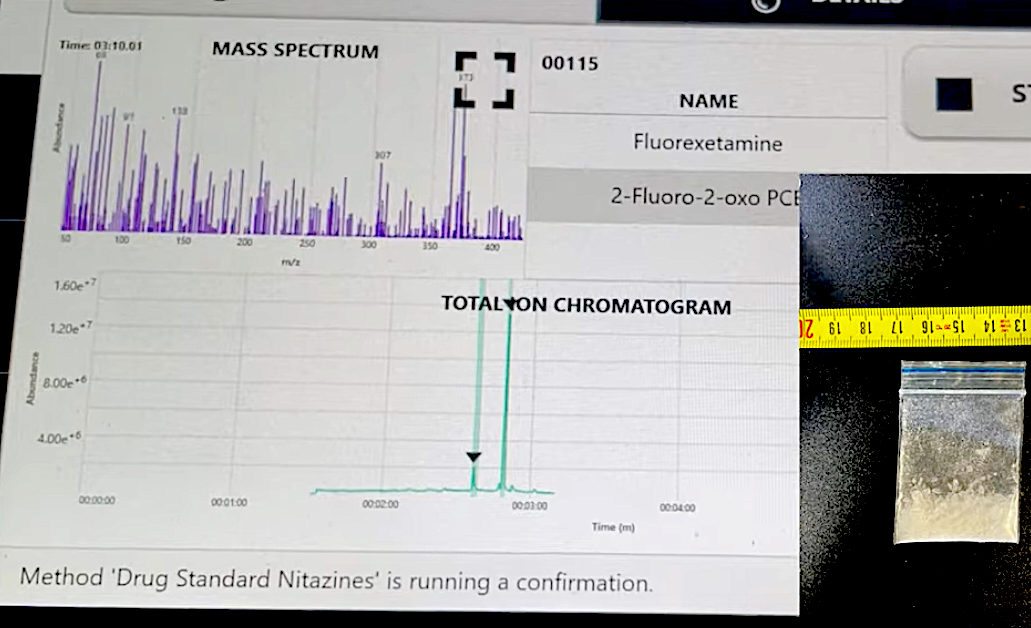

In March this year, over a deadly hot Labour Day weekend, our young team from the School of Population and Global Health tested a portable Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) device for the first time at an Australian music festival.

A GC-MS device can identify compounds and detect a class of dangerous synthetic opioids - nitazenes, which are up to 500 times more potent than heroin.

We used this equipment to identify an unknown substance on request from medical staff. But again, this was identifying drugs after they were taken.

Many medical staff asked why we couldn’t test before the drug was taken and potentially avoid harm in the first place?

In 2020, New Zealand was faced with a runaway regulatory problem.

A publicly funded drug checking organisation, called Know Your Stuff, was checking drugs before they were consumed.

Pre-consumption drug checking was progressing faster than the Government could legislate and before institutional guard rails could be put in place to measure the impact of drug checking.

The New Zealand Government responded by quickly passing legislation to legalise and regulate pre-consumption drug checking. That legislation has now successfully been in place since 2021.

The evidence from New Zealand drug checkers is that up to 75 per cent of people who received information about unanticipated drugs decided not to take them.

Business & Economics

Behind the numbers on illicit drug use

Similarly, the Victorian Government was faced with a choice between two viable, feasible approaches to managing drug-related harm: (a) pre-consumption drug checking and (b) post consumption drug testing.

It doesn’t take a university degree to know it’s always better to avoid harm in the first place than to be told about it later.

As researchers, we began talking to our undergraduate classes about this policy problem in back in 2021.

The nay-sayers say this is sending the wrong message. But governments have the choice of sending the ‘right’ message (i.e. “don’t use drugs”) that has no impact or a message that exercises its duty to prevent harm.

From this summer, mobile pill testing teams will set up at 10 festivals to run powder, pill and liquid testing to detect the presence of illicit substances.

This will be done before the drugs are taken.

The Government was presented with a choice based on the best available evidence, using the best available research and equipment from around the world.

Drug checking services will not stop all drug deaths, nor will everyone use them. International evidence suggests these services cater almost entirely for people who already use drugs.

But if this service can save just one life then it’s worth it. If it can provide information to a young person to moderate their drug use, it’s worth it.

The government made the right choice.

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.